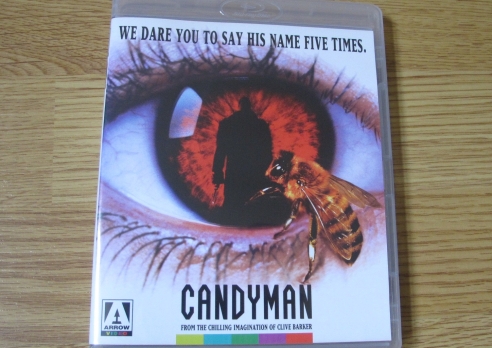

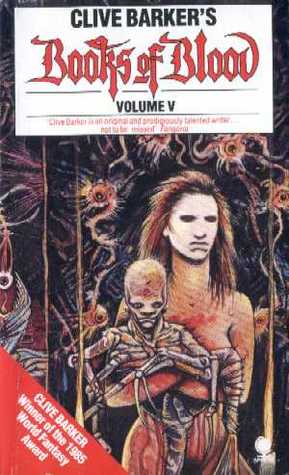

Bernard Rose’s 1992 film horror Candyman was adapted by him from Clive Barker’s 1985 short story “The Forbidden”, published in volume 5 of the groundbreaking Books of Blood.

Candyman transports the action from Barker’s Liverpool to Chicago, specifically to the “projects” (US term for “housing scheme”) of Cabrini-Green. In addition to the source material’s look at class, this – because Cabrini-Green’s population was overwhelmingly African-American – introduces the issue of race. The resulting film is a progressive, intelligent take on the 80s slasher movie.

Candyman himself – played with great charisma and elegance by Tony Todd – is a figure from urban myth, a hook-handed murderer who (in the film) appears before – and then eviscerates – anyone who says his name into a mirror five times. Virginia Madsen plays Helen, a grad student studying urban myths, who investigates the legend in the housing projects where Candyman is the spectre (literally) behind the walls.

***

From the opening credits, overlaid with Philip Glass’s stunning score, we are watching a film about distance and distancing: segregation. A “god’s-eye view” of traffic moves along freeways choked with cars, regimented and bounded.

The film’s black community is predicated on inhabitation. The cleaners at Helen’s university are black (and straight away, we have a class and race schism) and know each other from Cabrini-Green. By contrast, the white community is dependent on employment: Helen’s circle of friends are academics (in the source story, “their circle seemed entirely dominated by educated fools”), while the neighbouring apartment is unoccupied.

Helen’s friend Bernadette may be black but she’s middle-class, and her colour is no defence from the aggression they face when she and Helen arrive at the projects for their ill-advised exploration of the Candyman myth¹.

A powerful analysis on Arrow Video’s superb Blu-Ray release, by writers Stephen Barnes and Tananarive Due looks at how the film handles race. Although both find much to admire in the film, Barnes is unequivocal: this is “a film about black people for white people”. Nonetheless, because (by 1992) there were other cinematic interpretations of African Americans available, because “we can also be the hero” it was okay to be the monster, too.

That said, the fact that Candyman is killing blacks is problematic and doubtless due to “decisions behind the camera” being made by whites. The Evolution of Horror podcast discussion of the film suggests that “whites are the monsters”. In both film and story, Helen is involved in cultural appropriation at best, exploitation at worst. The story has her wondering “if there wasn’t a book, in addition to her thesis” in prospect, and in the film – as noted on the Arrow Video podcast – Helen is almost always smoking: tobacco, after all, was a slave crop.

***

And what of our anti-hero/villain? Candyman performs horrible deeds, but you can’t help warm to him. And that voice! But there’s a desperation to Todd’s Candyman: he is sustained by belief, as evinced by his wonderful soliloquy:

“I am the writing on the wall, the whisper in the classroom. Without these things, I am nothing. So now I must shed innocent blood…”

As writer (and Barker biographer) Douglas E. Winter notes, the film looks at how “as they fade away” gods and beliefs take on “a certain mystery and power”. In both texts, Candyman’s existence is dependent on belief:

“Our names will be written on a thousand walls…our crimes told and retold by our faithful believers. We shall die together before their very eyes and give them something to be haunted by.”

There is pathos in Candyman’s story (absent from “The Forbidden”) to explain this. The son of a slave, and himself a gifted artist, he fell in love with the daughter of a wealthy white man. Her outraged father hired thugs to punish the artist: they cut off his hand and smeared honey over his body. There were apiaries nearby, and the thugs left him to the bees. Cabrini-Green was later built there, and has been haunted ever since².

Horror has long explored the idea of places being forever tainted by atrocities in the past, whether in the form of a haunted house, a hotel – or pet cemetery – built on an Indian burial ground, and so on. “In The Flesh”, from the same volume of Books of Blood, is another example, where Pentonville Prison is a store of horrors from the past. What’s unusual about Candyman and “The Forbidden”, and part of what make them extremely interesting works of horror (rather than just satisfying fright-fests), is the exploration from a sociological viewpoint (and in the film’s case, a racial one).

In “The Forbidden”, we are in urban Liverpool. The story was published in 1985, just four years after the Toxteth riots. We are in the rotting underside of Thatcher’s supposedly shiny 1980s Britain. The denizens of this housing estate have been abandoned, by architects and city authorities³. No dockland penthouse flats for them.

Stephen Jones, on the Candyman audio commentary, observes that the estate is called Spector Street (not “spectre”). Like Hobbs End in Quatermass and the Pit, he suggests that the name has been corrupted over time, and the contemporary name conceals an original horror: that the “land itself [is] tainted”. Certainly, Helen is out of her comfort zone:

“The territory of the estate behind her was indisputably foreign, sealed off in its own misery”

As in the film, she meets a local single mother, Anne-Marie. Anne-Marie asks – several times – if Helen is from the council, if she might be there to help clean the place up. She makes no distinction between council and university: it’s all bureaucracy and representative of a different class, part of the establishment which has abandoned her and her neighbours.

Helen asks a pair of local women for more information on a murder that Anne-Marie is being circumspect about discussing. Their replies show uncertainty as to who they heard the story from, which adds a further layer of distance. They are also unsure of the when, and even the where. “It certainly wasn’t here. It must have been one of the other estates”. But crucially, they do not deny the story outright, and that’s enough of a hook for Helen to pursue the matter.

There’s a further difference between story and film in the role the estate’s community plays. In the film, they’re indifferent to the white middle-class universe. If rich whites want to come and indulge in ruin porn, then they can ride their luck. In “The Forbidden”, that would initially seem to be the case, too. But Helen realises – too late, of course – that she has been strung along. On a recent re-read (and before I listened to the audio commentary which also mentions it) I was struck by the parallels with The Wicker Man4.

She has been enticed, lured by the prospect of candy (the enigmatic graffiti “sweets to the sweet”). In the story, Anne-Marie’s baby is actually killed as a sacrifice and (DOUBLE SPOILER ALERT!) Helen burns just like Sergeant Howie on Summerisle. This act, though, is what will keep Candyman alive in folk memory, as per his quote above. Presumably, though, such acts need perpetuated from time to time:

“the thought chased its own tail: these terrible stories still needed a first cause, a well-spring from which they leapt”

In a perverse (and very Barker-esque) way, it’s a win/win situation: Helen achieves the posterity she sought, and simultaneously she is herself appropriated.

In the film, Helen makes her way into his lair and sees the fruit of his artistic talents. A mural – though bearing little resemblance to Virginia Madsen – appears to show Helen (“it was always you, Helen”) which suggests a theme of cyclic recurrence. This is not a hole being closed: as we see at the end of the film, in a neat reversal Helen now steps into Candyman’s shoes suggesting the start of a new cycle, in which a white middle-class spectre can exact revenge upon the white middle-classes.

Candyman has dated little. I haven’t seen the sequels (diminishing returns, by all accounts) but there’s a reboot planned. What I would like is a British adaptation, sticking to the original Liverpool locale. Any such production that was shot right now, and was properly in-tune with what’s going on in the UK, would be forced to examine “folk memories” and their consequences, and could be a timely addition to the disappointingly small canon of Barker adaptations5.

More Clive Barker at Into the Gyre:

- Killing the Parents: Clive Barker’s ‘Hellraiser’

- In praise of brevity: Clive Barker’s ‘Cabal’ and the anti-epic

- A Clive Barker Top 10

- 1990: Summer of cinema

Notes:

¹ Incidentally, amid all the graffiti which adorns the walls and stairwells is a painting of Godzilla powering through tower blocks: a subtle nod to another urban monster.

² In reality the site of Cabrini-Green, according to Stephen Jones in the audio commentary, was a gasworks in the late 19th Century, and was known locally as “little Hell”.

³ Barnes and Due also examine the role of Cabrini-Green (in Due’s words, “almost as much of a monster as Candyman”). Barnes observes that if Cabrini-Green is not contextualised – if there is no acknowledgement that these projects were built and situated in a manner specifically designed to exclude blacks from financial support and civic participation (redlining) – then there’s a risk that the precarity of the inhabitants appears due to something essential to them rather than imposed on them by circumstance.

4 ‘Folk Horror’ was in the middle of its years in the wilderness. After the initial late 60s/early 70s flowering, it lay largely dormant through the 80s as neoliberalism flexed its muscles (as Mark Fisher and Adam Scovell have analysed). That said, several of the Books of Blood stories touch upon similar ground (“Scapegoats” springs to mind; arguably the stunning “In The Hills, The Cities”, too). I’ve examined some of the Books of Blood stories through the prism of Folk Horror here.

5 Rawhead Rex, The Yattering and Jack, Hellraiser, Nightbreed, Candyman, Lord of Illusions, The Midnight Meat Train, The Book of Blood, Dread. Not that many, really, in 30 years: 7 from short stories and two (Nightbreed and Hellraiser) from novellas. No celluloid versions of any of his novels. Surely even the BBC could do an updated Damnation Game?

Sources:

Barker, Clive: Books of Blood volume 5 (Sphere, 1985)

Winter, Douglas E: Clive Barker – The Dark Fantastic (Collins, 2001)

Candyman (Arrow Blu-Ray, 2018)

Arrow video podcast: Candyman

The Evolution of Horror podcast: Candyman

3 thoughts on “Clive Barker: “Candyman”, “The Forbidden”, Place, Race & Time”