The Folk Horror Chain is a framework devised by writer and film-maker Adam Scovell in his essential study of the genre, Folk Horror: Hours Dreadful and Things Strange. For Scovell, Folk Horror can – among other things – be categorised as

“a work that uses folklore…to imbue itself with a sense of the arcane for eerie, uncanny or horrific purposes…[or] presents a clash between such arcania and its presence within close proximity to…modernity”¹

The Chain (which Scovell initially introduced here) consists of four “links”:

- Landscape

- Isolation

- Skewed moral beliefs

- Happening / summoning

Not all of the works analysed in his book necessarily contain all four: Scovell admits that the definition is flexible, and that it’s easier to recognise a Folk Horror work when you come across it than to define what constitutes one.

The original blossoming of work we now think of as Folk Horror almost exclusively dates from the very late 60s to the mid 70s. It is epitomised by the canonic ‘unholy trinity’ of three British-made films: The Blood on Satan’s Claw, Witchfinder General and The Wicker Man. Although these films differ in many ways (and only the first has any explicit supernatural elements), they are united by ‘dark goings-on in the countryside’. Works which are key exemplars of the Folk Horror aesthetic were generally produced after the irruption into popular culture of an interest in esoteric or pagan subjects. This can partly be traced to the aftermath of 1967’s psychedelic explosion and, particularly, when that explosion turned dark at the end of the decade. Although the occasional outlying work appeared later which showed its traces, what we would now classify as Folk Horror had died out by the late 70s.

By the mid 1980s, society and culture were in the middle of a huge transformation, the catalyst for which were the elections in Britain and America of right-wing governments armed with extreme economic agendas. It’s important to note now how much of a change Thatcher and Reagan heralded, because although theirs is the landscape we now occupy, it in itself was a sea-change from the post-war social contract (especially in Britain) which saw commitment from government of left and right to maintaining, by and large, the welfare state and nationalised industries. By common consent the thirty years after World War 2 saw the greatest period of stability and the smallest disparity in living standards in history. By 1985 however, when Clive Barker published the second three volumes of his Books of Blood, both political leaders had been comfortably re-elected, the great sell-off of those industries was underway, and in Britain organised labour – in the form of trade unions who had helped secure great improvements in the standard of living for working class people – was being symbolically destroyed as the year-long miners’ strike limped to a close.

Horror, in film and fiction, had been dragged out of it’s Poe/James/Wheatley-inspired mid-century cosiness by the likes of Stephen King and James Herbert, whose visceral novels arrived at a time of economic crisis (itself a catalyst for the new economic dogmas of the right) in the mid 1970s.

Horror – if it is at all to ring true – should always reflect the anxieties of its era. This new fiction was, as much horror throughout the ages has been, somewhat reactionary: the status quo is largely re-established at the end, notwithstanding any collateral devastation along the way. James Herbert’s novels – hugely enjoyable though they are, and despite the author’s protests that they’re apolitical – in particular depict a reactionary view of the world. An argument could easily be made which equates the rats of Herbert’s most famous books with the massed ranks of organised labour whose industrial action was a regular feature of the mid 70s. The heroes of Herbert’s books (and, later, those of Shaun Hutson) are lone, rugged males (who I suspect would vote Tory); “men’s men” unfailingly capable of bringing the female lead to climax through strictly penetrative sex during the inevitable – and frequent – sex scenes, which are always described from the point of view of the male gaze.

In the 1980s, following the success of Friday The 13th and Halloween, ‘slasher’ movies and fiction made up a sizeable part of the horror genre. These works placed sexually active youths as the victims, which echoed a conservative societal backlash against the permissiveness of the previous two decades, and was in keeping with the agendas of the governments of the day.

Clive Barker burst onto this horror scene – after a decade of producing dark, grand guignol-inflected plays – in 1984 with the first three volumes of his Books of Blood. With levels of gore and sex that were more explicit, more imaginative, and far more transgressive, than anything previously seen he heralded the arrival of a short-lived fad known as ‘splatterpunk’. Few of these works (by the likes of John Skipp & Craig Spector) approached the visionary quality – or even the morality – of Barker’s writing. Barker was quick to distance himself from the ‘splatterpunk’ tag as his works moved into the fantastique, but the early short stories with which he made his name are still startling, more than thirty years on. Barker’s work was broadly left-wing and, though he didn’t come out for several years, in hindsight were hugely influenced by queer and BDSM subcultures.

A further key to understanding much of Barker’s work, and an aspect of it that has had little critical attention, is his use of nomenclature and motifs from Christian belief:

“Biblical themes such as Revelation and Armageddon, run behind all my work, though my interest is in folklore and legends as much as it is in Christian iconography.”²

In this study, however, it’s the latter part of that quote I wish to investigate. Barker’s interest in folklore tends to manifest itself in an exploration of how we use beliefs and legends, and how we use stories. There are many Biblical references (Eden in Weaveworld; Midian and Baphomet in Cabal; Imajica is a re-telling of the life of Christ), but as far as ‘real’ folklore is concerned, there is very little of it in his fiction.

He instead consciously creates his own folklore within the context of his novels. In Cabal again, the town of Midian is a rumour shared by “people in pain”. In much of Barker’s work, the worlds of wonder and terror are often made manifest by forms of magic which belong more to the occult than to folklore. Although ideas of what constitute ‘folklore’ and ‘the occult’ can overlap, I would argue that ‘the occult’ implies an efficacious use of magic for the summoning of deities/figures (who may indeed also appear in the ‘lore’ of a people). The Hellbound Heart, I’d suggest, is a work in which the Cenobites (as they’re called in the film adaptation Hellraiser: in the novella they belong to The Order of the Gash), and their summoning via the Lament configuration box, belong to the occult rather than folklore: that is, they can be explicitly summoned by use of magic. ‘Occult’ suggests workings which are secret; lore, by definition, belongs to ‘the folk’ and may be (or may once have been) common knowledge. The Art, in The Great and Secret Show and Everville, is by this definition occult.

Before his novels, though, there were only the Books of Blood. Several of the stories contain some of the links in the Folk Horror Chain, but do not adequately “feel” like works of Folk Horror. It’s worth noting that Folk Horror – though the term did exist prior to Mark Gatiss’s popularising of it in the 2010 BBC series History of Horror – is a term used retrospectively. It isn’t, therefore, a genre that Barker would consciously have considered his works as belonging to, so the Folk Horror nature of these tales is – as with all 20th century works we now call “Folk Horror” – incidental.

***

The first story I’ll look at is one with a longer afterlife than some of the others, thanks to subsequent screen and comic-strip adaptations: volume 3’s Rawhead Rex. Shot through with a sense of humour so black as to be almost invisible this is a gleeful, spectacularly violent head-biting-off, child-eating festival of carnage, a (heavily) ironic feminist response to previous works of pagan terror such as those produced by Hammer.

The scene is rural Kent, forty miles south of London, in the village of Zeal (a name more Cornish sounding than Kentish, though it does mean the locals are – literally – Zealots).

“There’s been a settlement here for centuries, stretches back well before Roman occupation. No one knows how long. There’s probably always been a temple on this site…and there was a forest here. Huge. The Wild Woods…full of beasts”³

The story mocks the nouveau-riche of early Thatcherism: Zeal is fast becoming a weekend retreat for those relatively few who have done well out of turbo-charged capitalism. Slowly, the original population is edged out (priced out, or dying out). In this way, Barker suggests, local lore is forgotten.

The story’s opening sentences frame this takeover as the latest – the last, in fact – in a series of defeats suffered by Zeal, whether by Romans, Normans or during the Civil War. None of the previous defeats caused it to lose its identity.

A farmer (son of farmers before him, though ignorant of the history of his own lands) digs up a troublesome stone from a seemingly-blighted field. This inadvertently releases a monster, which had been buried alive centuries before. Although the local pub is called ‘The Tall Man’ the exact source of the reference is long-forgotten, but here it is, returned, hungry and bearing teeth. The farmer (“he knew the moment well…knew it from some nightmare he’d heard at his father’s knee”) is the first victim:

“Thomas Garrow just stood and watched. There was nothing in him but awe. Fear was for those who still had a chance of life: he had none.”4

The name of the creature is specific and deliberate: Rawhead is his name (yes, his head is ‘raw’ but it also refers to the head of a penis) and Rex his honorific: the story calls him “The King”.

“The inspiration for Rawhead Rex came from a tale from English folklore about Rawhead and Bloody Bones. I didn’t know any more about them but their names, but they evoked quite a lot of ideas. Rawhead is the mindless thing unleashed. I wanted to create a monster who had no niceties; he’s relentless, hungry, there’s no appeal for mercy, all you can do when you’re with him is run. The image I had was a figure with the body of a human being and the mind of a hungry animal.”5

Rawhead lives in an eternal present of “his hunger and his strength, feeling only the crude territorial instinct that would sooner or later blossom into carnage”6: toxic masculinity untamed and unbound.

Barker’s universe, for all it’s exploration of Christian symbolism, is a godless one. Declan Ewan, verger at the local church, is quick to realise that Rawhead’s appearance is as close to a Second Coming as he’s ever going to get. There’s a carving on the altar – hidden in plain sight – of Rawhead’s incarceration underground in the fourteenth century.

Although other Barker stories offer a form of transformation at the ending, rather than the more traditional expelling of a threatening Other, this one does not: Rawhead is destroyed with a finality previous generations of Zealots were unable to provide. We are also, unusually (although there is an excellent precedent in Frankenstein), privy to what goes on in Rawhead’s mind. Although this might not make us empathise with him, it gives him more substance than the cartoon he could have been in less-skilled hands. What the story does that’s unusual is to frame the good v bad in terms of sexuality. Masculine energy here is sheer destructive appetite: Rawhead fears women, and menstruating women are especially taboo. That said, “the feminine” is not itself portrayed in positive terms other than that it is an antidote to Rawhead’s raging Id; but that in itself is surely a good thing.

What defeats Rawhead is a stone carving – like a sheela-na-gig – that a bereaved father smashes into his skull.

“The stone was the thing he feared the most…it was life, that hole, that woman, it was endless fecundity. It terrified him”7

It’s worth noting that although in theory femininity destroys Rawhead, the symbol of it is still wielded by a man. Ron Milton’s victory over Rawhead can also be seen symbolically – he is one of the incomers from London – as Zeal’s real, final defeat: it belongs to the outsiders now. Rawhead, in spite of everything, was a spirit of the place.

The George Pavlou-directed 1986 adaptation of Rawhead Rex relocated the action from Kent to County Wexford in Ireland. Adam Scovell, in a chapter devoted to what he calls “Pulp Rurality”, calls the film “flawed”, which is generous. For him, it “fails to capture the essence of Clive Barker’s original story and its ruralism.”8

It’s fun in a watch-with-friends-over-beers kind of way: the production values are that of an early 80s ITV children’s drama; the acting, tonally, is all over the place – no two performances seem to be from the same film – and the monster is, well, shit.

That said, there are a few good images and it romps along at a good pace (Rachel Prin does a good analysis of it here). Barker complained that only about seven of his lines survived into the film. We should, however, be grateful that Rawhead Rex is as rubbish as it is, because without such a wounding experience Barker would never have been motivated to try to do better himself and thus give us Hellraiser.

There’s a comic adaptation – in common with many of the Books of Blood – from the early 90s. Although Barker’s prose lends itself to vivid imagery, few of the comic versions work as comics. The artwork is almost unfailingly superb, but so much of the (elegant, rhythmic) prose is retained that the marriage of the two works against strengths of the comic format.

However, Les Edwards and Steve Niles’s re-telling of Rawhead Rex is one of the stand-out comic versions of Barker’s work. Edwards’s art is stunning, and the look of the monster is much more in line with what the story suggests than the film: it actually looks like a monstrous rampaging penis with teeth. Which is exactly what it should be. Just enough of Barker’s careful prose is retained (in contrast to, say, Twilight at the Towers where so much text is needed it blots out the visuals, which kind of defeats the purpose) and the beats are structured perfectly.

Also in volume 3, Scape-Goats, as the name suggests, is partly a story about blame and responsibility. Two squabbling couples are on a boating holiday in the Hebrides. Barker himself spent summers on Tiree as a child, a landscape he would give a mystical dimension in the under-rated 1996 novel Sacrament. Filled with barely-concealed loathing for each other, Scape-Goats‘ travellers run aground on an unmarked island. “It’s not on any of the charts” notes one of the men in a (perhaps deliberate) echo of Han Solo in Star Wars when the Millenium Falcon is pounded by asteroids. Fittingly, these doomed holidaymakers will shortly suffer a similar fate.

The island is grim, lifeless; it infects even the on-board food with its malaise. I’ve never seen the word “slop” used so many times: the food is slop, the waves slop; all is a turgid, rotting waste. The island’s flies let themselves be trodden to death; there are sheep in a pen, the only other lifeforms. Sacrifices; scapegoats. Ray discovers that the island is a burial mound for those hundreds of sailors killed by torpedoes in World Wars.

This story has all the links of the Folk Horror Chain; the skewed morals may equally refer to the decadence of the tourists as much as the superstition of the people who offer up the sheep. And when Jonathan kills one of the sheep (in much the same way as Ron Milton dispatched Rawhead), the “happening” is set in motion.

“The beach had been flexing its muscles, tossing small pebbles down to the sea, all the time strengthening its will to raise this boulder off the ground and fling it at Jonathan.”9

Here, it’s noteworthy that the land itself is malevolent, taking vengeance on those who violate the slumber of those who have been entrusted to it. Frankie – the narrator – meets a local, come to feed the sheep, who tells her that the scapegoats are there as an act of remembrance. Together they try to escape the shower of rocks that has already wrecked the boat and killed Frankie’s companions.

Unusually for Barker, this tale is told in the first person, a mode whose conventions (though this particular trick has been repeated many times since) make the finale of the story a real shock. It’s the sense of transformation at the climax – soon to be a typical Barker trope – that makes this somewhat formulaic (though still creepy) story noteworthy.

***

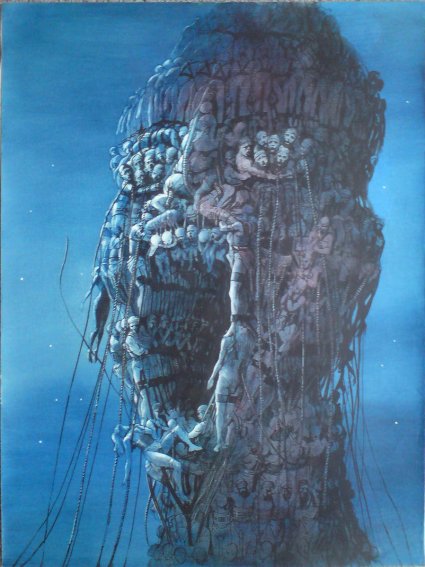

By contrast, the first volume of Books of Blood contained what in the 1980s was seen as the stand-out story: the startlingly original In The Hills, The Cities. Deep in the Yugoslavian hills, every ten years the citizens of Popolac and Pudojevo undertake a ritual battle unlike any other. Bickering lovers Mick and Judd (further proof that holidaying together is, for Barker, the quickest way to end a relationship) are touring the region, and realise they actually loathe each other. Judd is a right-wing bigot: in Mick’s words “mind-blowingly boring; killingly, love-deadeningly boring”10. Mick, for Judd, is shallow: “his mind was no deeper than his looks; he was a well-groomed nobody”, but a nobody who finds a sense of self at the end.

The hills of Yugoslavia have endured drought; the population is weakened by the “stale heat”. The ritual – in which the entire populations of the villages bind themselves together to form huge giants – is held in good spirit, but the condition of the people, especially those of Podujevo, is causing concern: made less resilient by famine, these communal/-ist giants are only as strong as their weakest constituent. Further, the Podujevo organiser has recently died and her daughter has inherited the post: a sign that the old ways are perhaps coming to an end. But the show must go on:

“By noon they were gathered, the citizens of Popolac and Podujevo, in the secret well of the hills, hidden from civilised eyes, to do ancient and ceremonial battle.”11

The hills are a well from which shortly only blood will flow. Mick and Judd miss their turn and, mis-hearing the footsteps of the assembled giants as thunder, or gunfire, see a river of blood gush from the hills. Podujevo has fallen; the weakness has spread throughout the frame and the giant has toppled, hurtling “thirty-eight thousand, seven hundred and sixty-five” souls to their death. The impact on Podujevo’s enemy is immediate. The populace of Popolac stare

“at the ruins of it’s ritual enemy, now spread in a tangle of rope and bodies on the impacted ground, shattered forever”12

and the remaining giant stumbles away. The horrific sight has transfigured the gathered individuals into a single entity in mind as well as body:

“They became, in the space of a few moments, the single-minded giant whose image they had so brilliantly re-created. The illusion of petty individualism was swept away in an irresistible tide of collective feeling – not a mob’s passion, but a telepathic surge that dissolved the vision of thousands”13

It’s this hive-mind that will finally end Mick and Judd’s fragile relationship. Judd’s death is an accident: his head sheared off by a stone dislodged as the giant crushes a house; his death a mirror to the image he’d had earlier as he strode through a field, when mice had been sent

“scurrying through the stalks as the giant came their way, his feet like thunder…he meant no harm to them, but then how were they to know that?”14

Like Garrow in Rawhead Rex, the holidaymakers’ experience is utterly transforming, an epiphany:

“neither fear nor horror touched them now, just awe that rooted them to the spot…this was the apex – after this there was only common experience”15

Mick runs to join Popolac: “anything to catch this passing miracle and be part of it…better to die with it than live without it”16 while Judd’s corpse becomes food for a fox, his body a home for maggots.

This is an unusual story in many ways: entirely original and without any supernatural element, the horror here is the death of Podujevo; Judd is collateral and Mick finds transcendence: what can beat being “a hitchhiker with a god”? This coming to terms with extremity and finding transformation therein is typical of Barker, and part of what makes his work much more radical than many horror authors. It also, horribly, prefigures the very real terrors that the Yugoslav hills were to witness in the early 1990s.

As regards the Chain, arguably there are no skewed morals here, unless your politics are so far to the right that any collective endeavour is inherently evil. If the landscape per se is less significant than in, say, Scape Goats, likening it to a “well” suggests it’s a source of sorts for the behaviour contained within it, and the isolation of the villages has helped to breed this ritual. As for the “happening”, the reader is aware of it from the beginning and the travelling pair only stumble across the aftermath once the ritual has gone catastrophically wrong.

Where Folk Horror normally places the modern in stark contrast to a threatening resurgence of the old, one could argue that – rather than being Barker’s version of Hobbes’s Leviathan – technically these villages (whose forms literally resemble “the body of the state…the shape of our lives”17) are the communist dream made manifest, and what, in the twentieth century, could be more modern?

***

Also in Volume 1, Pig Blood Blues is at first glance perhaps an atypical Folk Horror, but all the links in the Chain are there. Ex-cop (colloquially, a “pig”) Neil Redman starts a new job at the aptly-named Tetherdowne remand centre for adolescent boys. Here, we immediately have isolation: what could be more isolated from society than what is – in all but name – a prison?

Redman tries to assert his authority: “Yes son, I’m the pig”18 shows straightaway that he is not cowed, that name-calling has no effect. If the inmates are to get under his skin, they must use other methods.

“Landscape” is a less active element than in other stories, though the sense of a closed-off society is suggested, and indeed we never see or hear the outside world:

“it was as stale outside as inside, as though the whole world had become an interior: a suffocating room bounded by a painted ceiling of cloud”19

However, the grounds of Tetherdowne are large, and include a farm. The centrepiece of this – and of the story – is the pig sty and, at its black heart, the pig which acts as Tetherdowne’s de facto moral compass. Even Redman is impressed:

“the sow was beautiful, from her snuffling snout to the delicate corkscrew of her tail, a seductress on trotters”20

But in a location by necessity founded on principles of inviolable hierarchy, such admiration doesn’t go both ways:

“her eyes regarded Redman as an equal, he had no doubt of that, admiring him rather less than he admired her”21

One of the boys, the weak and “virginal” Lacey, tries to escape. He’s haunted by the presence of a previous escapee, Hennessey, who Redman discovers (after much obfuscation by his peers) hanged himself in the pig sty. His dream of never growing old (“to live forever, so he’d never be a man, and die” – Peter Pan is Barker’s favourite book) was thus achieved, albeit with unintended consequences: his voice lives on, literally, because the pig now speaks with Hennessey’s tongue.

The pig, all powerful, is worshipped. Inmates bring her food while rightly cowering in fear – she may “accidentally” take their fingers off as she feeds. She’s had a taste, though, of human flesh – Hennessey’s – and wants more.

Redman stumbles across “a congregation” gathered at the sty, lit by candles, like an altar: “it was eerie, to see those godless delinquents so subdued by reverence”22. Godless, but – typically for Barker – not without a deity of some form. Redman, unlike Helen in The Forbidden (see below) is not transformed, just eaten. The moral, the motto of Tetherdown even, is revealed to him in his final moments. “This is the state of the beast, to eat and be eaten.”23

***

I’ve written elsewhere about volume 5’s The Forbidden in relation to its big-screen adaptation Candyman, but because much of the analysis is also relevant to a study of the story as it embodies aspects of the Folk Horror Chain, I re-use some of it here.

Postgraduate student Helen is researching graffiti in a downtrodden council estate in Liverpool, and trying to find an original angle for her research. She meets a local single mother, Anne-Marie. Anne-Marie asks – several times – if Helen is from the council, if she might be there to help clean the place up. She makes no distinction between council and university: it’s all bureaucracy, and representative of a different class: part of the establishment which has abandoned her and her neighbours.

Helen probes a pair of local women for more information on a murder that Anne-Marie is being circumspect about discussing. Their replies are evasive, show uncertainty as to the provenance of the story, the timeframe it happened in, and even the location: “It certainly wasn’t here. It must have been one of the other estates”24. But crucially, they do not deny the story outright, and that’s enough of a hook for Helen to pursue the matter.

It’s notable that this tale is not in a rural backwater, but one of England’s largest cities. Does that define it as belonging to the “Urban Wyrd” rather than “Folk Horror”? There’s a line of thought (below) which suggests the two are not simply the same thing in different backgrounds, but significantly for our purposes, The Forbidden includes all the links of the Chain.

Stephen Jones, on the audio commentary of Candyman, observes that the estate is called Spector Street (not “spectre”). Like ‘Hobbs End’ in Quatermass and the Pit, he suggests that the name has been corrupted over time, and the contemporary name conceals an original horror: that the “land itself [is] tainted”. This is just one of many ways that Barker creates a sense of distancing and isolation. Certainly, Helen is out of her comfort zone:

“The territory of the estate behind her was indisputably foreign, sealed off in its own misery.”25

This is a distance caused by capitalism (Barker once described himself as “by nature a socialist”26). The residents are it’s victims. The myth they share – that of the mysterious “Candyman” – is partly a coping mechanism. As one character observes, “maybe if they didn’t tell you their stories…they’d actually go out and do it”27 (but of course in the end, they do “do it”: the estate is complicit in what happens to Helen).

So we have a sense of isolation, itself partly a function of the landscape itself. It’s a landscape from which the architects have retreated, leaving “surroundings so drab, so conspicuously lacking in mystery”28. Yet Helen is investigating a mystery: the graffiti, among which is a gnomic slogan “sweets to the sweet”29.

The abandoned have folk heroes in whom they place more belief than in any saviour, messiah or institutions, and this slogan pertains to Candyman, whose dandy-like appearance is in contrast to Tony Todd’s empathetic murderer in the film version. Thus the story’s “happening” reveals the “skewed moral beliefs” held by the isolated estate-dwellers. Helen realises – too late, of course – that she has been strung along. Just like Sergeant Howie in The Wicker Man, she has been enticed: lured by a mystery which only recedes the more she pursues it. Anne-Marie’s baby is actually killed as a sacrifice and Helen burns, again just like Sergeant Howie on Summerisle. This act, though, is what will keep Candyman alive in folk memory. Such acts need perpetuated from time to time:

“the thought chased its own tail: these terrible stories still needed a first cause, a well-spring from which they leapt.”30

In a perverse (and very Barker-esque) way, it’s a win/win situation: Helen achieves the posterity she sought to win by her research, and simultaneously she is herself appropriated by the estate, feeding the consoling myth.

***

There are other stories in the Books of Blood which contain several links in the Folk Horror Chain, but whose urban location mitigates against them being considered Folk Horror. For example In the Flesh, set in Pentonville Prison, arguably contains all of the links but configured in such a way that the “folk” element is largely absent. Could these stories then be considered to belong to the Urban Wyrd?

Let’s examine a few definitions of this, Folk Horror’s big-city cousin. First, from the preface to Folk Horror Revival: Urban Wyrd volume 1: Spirits of Time:

“a sense of otherness within the narrative, experience or feeling concerning a densely human-constructed area…with regard to another energy at play or in control; be it supernatural, spiritual, historical, nostalgic or psychological. Possibly sinister but always somehow unnerving or unnatural.”31

The foreword to the same book posits that the Urban Wyrd is “not simply Folk Horror in a built-up environment…though the Urban Wyrd may indeed share some characteristics with Folk Horror.” Bluntly, Urban Wyrd would seem, then, to share the first and final links in the Folk Horror Chain (an urban “landscape” and a (possibly sublimated) “happening/summoning”).

Adam Scovell, in a separate introduction in the same book suggests Urban Wyrd includes

“media that re-occult and remythologise the environment…different in tone and flavour [from Folk Horror, and]…interconnected but not the same.”32

Stories such as The Midnight Meat Train, Human Remains, and The Madonna could therefore benefit from an examination in this light, but that lies beyond the scope of this essay.

As I said in my introduction, because the genre of Folk Horror is one that has been bestowed retrospectively, it’s unlikely Barker thought of the stories in that way. Although I quoted him above in relation to folklore, Barker’s concerns unsurprisingly differ from those of film-makers from a decade-and-a-half before. And, as Folk Horror consists of tropes which previously existed, it’s almost inevitable that horror writers would produce works which with hindsight are “accidental” Folk Horror, such as Barker’s fellow Liverpudlian Ramsay Campbell’s Midnight Sun (1990).

Barker, for a figure who enjoyed such huge popularity and a high profile in the late 1980s and early 1990s, is a writer whose work has had less critical analysis than would perhaps be expected. Today, he is a far less visible presence, though much of what he pioneered in the 80s has become almost mainstream within horror culture. There is ample scope for further exploration of his use of belief (which I have merely touched upon here), and of landscape and topography.

Notes:

¹ Scovell, Folk Horror, p7

² https://www.clivebarkerarchive.com/cabal-article

³ Barker, Books of Blood vol 3, p53

4 ibid, p42

5 Fangoria Poster Magazine, No 2, 1988, quoted at http://www.clivebarker.info/ints88b.html

6 Books of Blood vol 3, p46

7 ibid, p80

8 Scovell, p95

9 Books of Blood vol 3, p133

10 Books of Blood vol 1, p122

11 ibid, p131

12 ibid, p135

13 ibid, p139

14 ibid, p125

15 ibid, p147

16 ibid, p148

17 ibid, p141

18 ibid, p63

19 ibid, p78

20 ibid, p66

21 ibid, p66

22 ibid, p79

23 ibid, p85

24 Books of Blood vol 5, p16

25 ibid, p5

26 Harper, Leanne C.: “Clive Barker: Renaissance Hellraiser” in Jones, Shadows in Eden, p207

27 Books of Blood vol 5, p28

28 ibid, p12

29 ibid, p7

30 ibid, p28

31 Paciorek, Urban Wyrd – 1. Spirits of Time, p7

32 ibid, p11

Sources:

Barker, Clive: Books of Blood, volumes 1-3 (Sphere, 1984)

Barker, Clive: Books of Blood, volumes 4-6 (Sphere, 1985)

Jones, Stephen (ed.): Clive Barker: Shadows in Eden (Underwood, 1991)

Paciorek, Andy et al: Folk Horror Revival: Urban Wyrd – 1. Spirits of Time (Wyrd Harvest Press, 2019)

Scovell, Adam: Folk Horror – Hours Dreadful and Things Strange (Auteur, 2017)

Arrow Video: Candyman Blu Ray (2018)

http://www.clivebarker.info/ints88b.html

https://www.clivebarkerarchive.com/cabal-article

2 thoughts on “The Folk Horror Chain in Clive Barker’s “Books of Blood””